|

William Nordhaus was awarded the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences because of his decades' effort to integrate climate sciences into economic models. His Dynamic Integrated Climate and Economy (DICE) is used to explain how Greenhouse Gases emissions if not tamed could lead to catastrophes down the road. This pioneering effort is not immune to criticism. Using climate-economy integrated models to design and implement specific climate policies is subject to misuses, as Robert Pindyck contended. According to Pindyck, modeler's limited knowledge about climate sensitivity and arbitrary selection of functional forms and parameter values do not make results from complicated models more valid than modeler's own "expert" opinion.

0 Comments

6/21/2018 0 Comments Visit at Princeton I enjoyed the visit at the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering at Princeton University. I have had great discussions with Professor Lin and her Hurricane Hazards and Risk Analysis Research Group.

I am honored to be invited to give a seminar talk, entitled "Understanding Human Judgement on Environmental Risks and Hazards in a Geographic Context," at the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering at Princeton University on June 21.

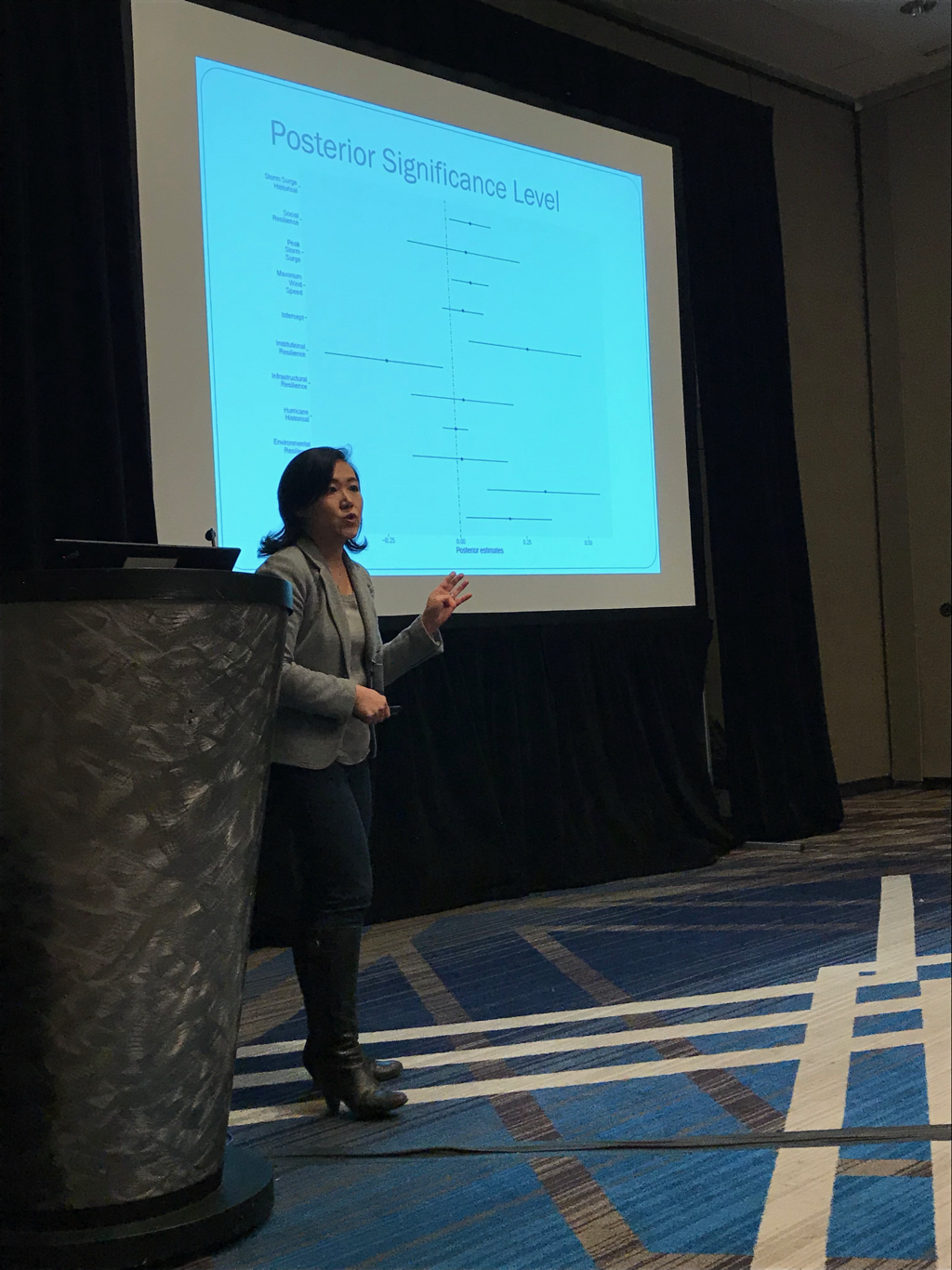

The abstract of the talk is as follows: "The coupling effects of changing climate and rising concentration of population and assets in the coastal regions have increased the threat of potential damages. There is an urgent need for coastal communities to prepare well for future hazards through mitigation and adaptation measures. A growing number of empirical studies have found that peoples’ motivation of voluntary risk mitigation and adaptation is low unless actual risk can be perceived. Risk perception is thus the precondition for adaptive behavior. It is of both intellectual and practical interests to study what affects individuals’/communities’ risk perceptions. In this talk, I will present four of my previous studies. The first three studies are focused on the individual level and the fourth on the aggregate level. I will start with understanding how local weather and climate affect American public risk perceptions of climate change. I will then discuss how the spatial context represented by past flooding events and estimated flooding risks influence costal residents’ voluntary flood insurance purchase decisions and their support for flood adaptation policies. As many policies are designed and implemented at an aggregate level (i.e., state, county, city), it is necessary to examine aggregate-level risk perceptions. In the fourth study, I will focus on how the contextual hurricane risks in conjunction with community resilience shape county-level perceptions of hurricane-related risks. I will end with a research agenda linking communities’ perception with contextual risks and community resilience. I contend that the cognitive dimension including both risk perceptions and perceived adaptive capacity is not represented in any of the existing community resilience indexes, and therefore needs to be measured, quantified, and incorporated into a more comprehensive index." Our new paper on aggregate perceptions of hurricane risks has been published on the Annals of American Association of Geographers.

Despite his blunt but abrasive style, Nassim Taleb is a master of conveying complicated ideas and revealing hidden patterns that would otherwise easily escape many people’s eyes. Using observations, historic stories and anecdotes with satire and ridicule, he aptly describe statistics and risks in a way that is not elusive and confusing to laymen. A voracious reader, he is able to integrate great ideas from philosophy, statistics, religion, economics, psychology, political science, medicine into his telling of Incerto. His first two books Fooled by Randomness and Black Swan surround around the theme of fat tail risks that most people are likely to ignore during “normal” times and therefore tremendously underestimate these risk. These risks nevertheless have enormous impacts on societies. If these two books are meant to identify the problem, his latest two books Antifragile and Skin in the Game are concerned with strategies to mitigate the problem. The metaphor “skin in the game” is used to describe any disincentive that exist in a system to prevent individuals from adopting certain reckless measures that would incur damages. It seems to be the optimal way he offers to cope with any systematic risks.

In modernity, many enormous risks go unnoticed for many years because these risks are created, managed, and in some cases intentionally veiled by an ever growing class that has no skin in the game nevertheless makes crucial decisions for others. According Taleb, bureaucrats, policy wonks, politicians, bankers, corporate executives, journalists, and academics all belong to this class. That many hidden fat tail risks end up blowing up to the faces of these so-called elites is precisely due to their safe insulation from these risks. One can only learn from bearing the direct consequences of one's own mistakes. No personal consequences, no sincerity; no skin in the game, no effective risk management. In order to mitigate these risks, disincentives thus need to be put in place in the system. Everyone needs to put their skin in the game. This prescription seems to resonate with the prospect theory that one is more averse the risk than embracing the reward of equal amount. This asymmetry is reminiscent of evolution.To put it plainly, we can only be so happy but the other side is the end of our existence. Evolution is an emotionless, cruel (from an individual life's perspective), but super effective machinery. Systems improve by eliminating the weak. He further suggests that the only way for society to function well has got to be from bottom up, not top down. That's why globalization, interventionism, hierarchical bureaucracy have not and will not work. He also explains Elinor Ostrom's pioneering work on self-governance to address the "tragedy of the commons" as follows, "the skin-in-the-game definition of a commons: a space in which you are treated by others the way you treat them, where everyone exercises the Silver Rule." If such a commons gets established by explicit or implicit rules, the resources can be managed well to avoid a tragedy of the commons caused by individuals' pursuit of self interests while ignoring others' welfare. It seems that Taleb interprets Ostrom’s work as evidence for decentralization of governance. But Ostrom’s theory is characterized as “polycentricity.” The optimal scale of governance should correspond to the problem of the same scale. For instance, the global scale of climate change essentially requires international cooperation. In this book, he debunks the myths of “majority rule,” “Pascal Wager,” among others. He ridicules the “Intellectual Yet Idiots.” He instructs that we should choose surgeons that do not look like surgeons. He distills the wisdom of time into the expert called Lindy. The reason why it is the stubborn minority that dominates is because this smaller group has more at stake, in other words, skin in the game. He uses the example that how one family member with peanut allergy can spread the “no peanut” rule first to the household and later to whichever social circle this member happens to be at. The reason why “Pascal Wager” is not true is because it cost a lot for someone to believe in God. Faith is not cheap talk. Religious people have put their necks on the line to be truly faithful unless they are hypocrites. Some quotes from the book: "You will never fully convince someone that he is wrong; only reality can." "There is no evolution without skin in the game." "The curse of modernity is that we are increasingly populated by a class of people who are better at explaining than understanding." "What is rational is what allows the collective - entities meant to live for a long time - to survive." "Things designed by people without skin in the game tend to grow in complication (before their final collapse)." "The main idea behind complex systems is that the ensemble behaves in ways not predicted by its components. The interactions matter more than the nature of the units." Risk perceptions have been intensively studied because they are believed to induce behavior change, which would have consequences in the world. Now, a group of researchers from multiple disciplines have taken this idea one step further by linking human behavior model with climate model. Their study has just been published on Nature Climate Change. It is exciting to see this kind of integrative approach in the climate research field. The complexity of climate change really requires concerted efforts of scientists from a wide range of disciplines.

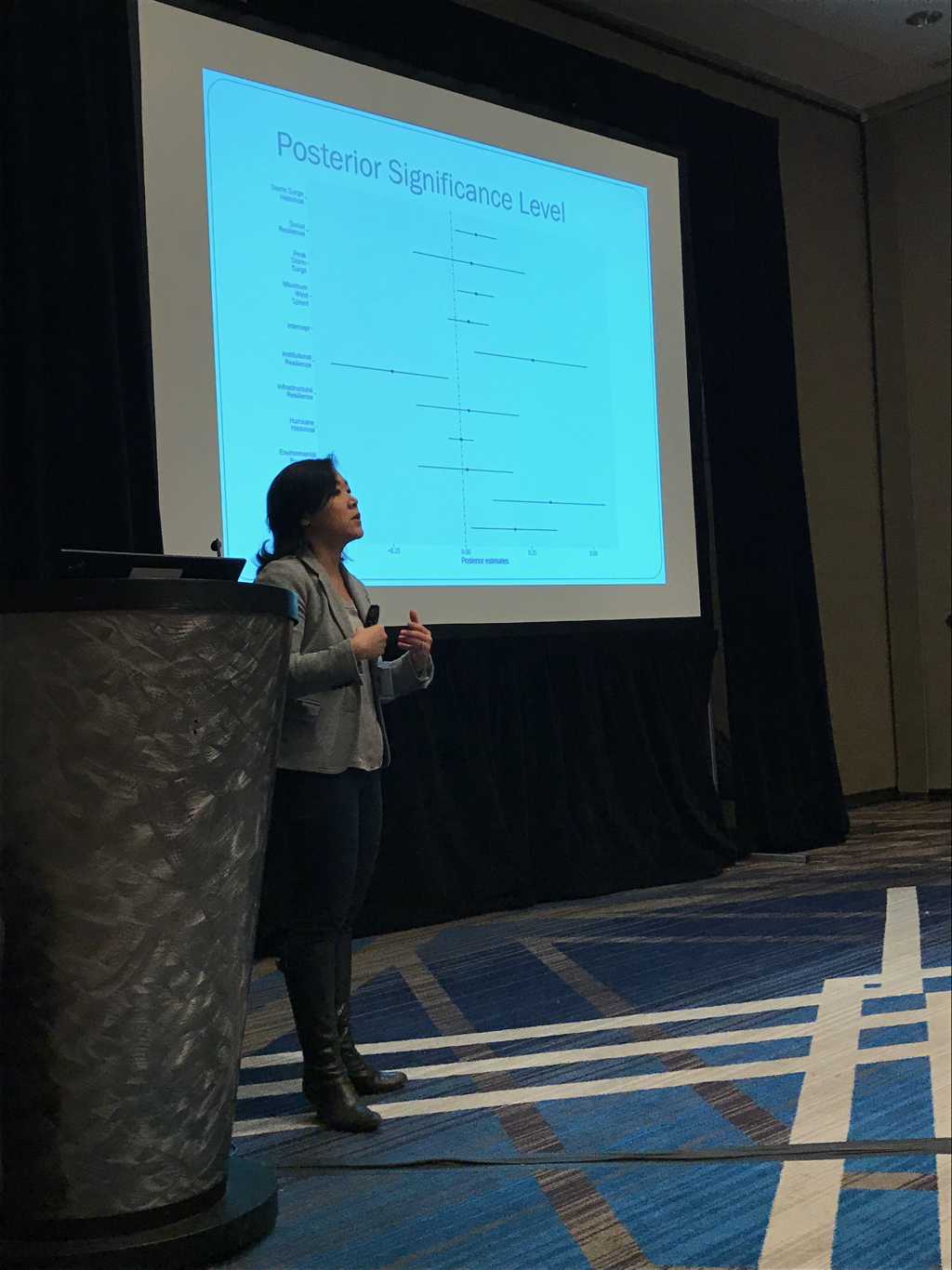

I presented our study on community resilience and county-level perceptions of hurricane risks along the US Gulf Coast at the 2017 Society for Risk Analysis annual conference in Arlington, VA.

3/4/2017 0 Comments Perception and risk assessmentThe Magazine of the American Society of Civil Engineering has reported on our paper on perceptions of shifting hurricane strength among Gulf Coast residents.

The News at Princeton put out a newsletter about our paper on perceptions of changing hurricane strength that was published on the International Journal of Climatology: www.princeton.edu/main/news/archive/S47/20/56S93/index.xml?section=topstories

8/21/2016 0 Comments Louisiana's Epic Flood The southern Louisiana was absolutely devastated by an epic flood last week. Tens of thousands of people were displaced due to this historically unprecedented flooding event. 13 people died of this event, 40,000 homes were damaged, and 20 parishes were declared Federal Disaster Area. For many residents in these communities, this flood was even more destructive than Hurricane Katrina. Here, I post some pictures of the neighborhood I used to live in. The street was full of trash in the aftermath. Inside the house after the water receded After the worst natural hazard since Super Storm Sandy, many coastal communities are facing a long recovery. When interviewed by NPR's On Point, my former doctoral advisor Dr. Barry Keim, Louisiana State Climatologist, was asked if this epic flood was related to climate change, Dr. Keim pointed out that it was difficult to determine an absolute link between climate change and a single event. His response highlights the key to understanding climate change. By definition, climate change refers to “a change in the state of the climate that can be identified by changes in the mean and/or the variability of its properties, and that persists for an extended period, typically decades or longer," according IPCC. Lay persons are more likely to be influenced by isolated extreme weather events when making judgments about climate change. More frequent extreme weather events, though, collectively form a pattern that can be attributed to climate change.

The economic damage from flooding in the coastal areas has dramatically increased over the past several decades. One effective way to mitigate excessive economic losses from flooding is to purchase flood insurance. In reality, only a minority of coastal residents however have taken this preventive measure. In order to understand the driving force behind individuals' decision to voluntarily purchase flood insurance, my coauthors and I examine how external influences and perceptions of flood-related risks together with socio-demographic factors affect this voluntary behavior in the U.S. Gulf Coast by using survey data merged with contextual data. This paper has been published on Water Research. Our findings indicate that estimated flood risks conveyed through FEMA's flood maps, intensities and consequences of past storms and flooding events, as well as perceived flood-related risks significantly affect individuals’ voluntary flood insurance purchase behaviors. The finding about FEMA's flood maps has significant policy implication that FEMA’s flood maps have been effective in conveying local flood risks to coastal residents, and correspondingly influencing their decisions to voluntarily seek flood insurance. Flood maps therefore should be updated frequently to reflect timely and accurate flood risks. |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed